Lost cities have long been the subject of fascination. Places like Atlantis and El Dorado have inspired all sorts of wild theories and deadly expeditions, to no avail. Others, like Troy, Petra, Memphis or Machu Picchu, have since been rediscovered. When it comes to lost cities, we tend to think of mysterious, faraway places. However, the Old Continent has its share of them too. Some of these long-lost European cities have only recently been discovered by chance, others are still missing, and some have entered the realm of myth and legend.

10. Sevtopolis (Bulgaria)

Founded sometime in the last quarter of the 4th century BC by King Seuthes III, Seuthopolis was the capital of the Odrysian Kingdom. It was a Thracian kingdom that arose largely due to the Persian retreat from Europe following their failed invasion of Greece in 479 BC and the power vacuum they left behind. A long-time ally of Athens, the Odrysian Kingdom became the largest political entity in the eastern Balkans, encompassing much of today's Bulgaria, northern Greece, southeastern Romania, and European Turkey. However, until the founding of Seuthopolis, there was no fixed capital.

Lost for centuries, Seuthopolis was only discovered in 1948 during the construction of the Koprinka Dam in the Rose Valley in central Bulgaria. Archaeological excavations revealed Seuthopolis as an elite Thracian settlement with numerous Greco-Hellenistic influences. Although Seuthopolis is distinct enough to be equated with a true Hellenic polis, it had Greek-style houses and buildings. It also had two main roads that intersected in the center of the settlement, forming an agora. Most of the streets were paved, had underground drains, and were built in a grid pattern, creating rectangular islands.

But unlike typical Greco-Hellenistic cities, the common people of Seuthopolis lived outside the city walls. Its buildings were generally spacious and luxurious, with plenty of space between them. The royal palace was also separated from the rest of the city by walls and watchtowers. This indicates a lack of "national unity" in the Odrysian kingdom, as the king was more of an overlord of other tribal leaders. Another distinctive feature is that each house had its own altar, known as an eschar, common in the Middle and Late Bronze Age. Other similar archaeological and historical evidence indicates that Seuthopolis was a religious center, with Seuthes as a priest-king.

9. Jomsborg (Poland or Germany)

Recently popularized by the second season of the series "Vikings: Valhalla" , Jomsborg was a fortified settlement and home of the Jomsvikings. Situated somewhere on the southern coast of the Baltic Sea, most likely in what is now northwestern Poland, Jomsborg is believed to have existed between 960 and 1043 AD.

Its inhabitants, the Jomsvikings, were a group of Viking warriors who, although they had strong faith in the ancient Norse gods, were mercenaries and fought for whoever paid them the most. Some claim that the Jomsvikings were an elite group of men between the ages of 18 and 50 who adhered to a strict code of conduct. They were only allowed to join after defeating another participant in single combat. They were also forbidden to quarrel among themselves, show fear, flee in the face of an equal or inferior enemy, or curse their brothers in arms, among other things.

However, the exact location of Jomsborg remains somewhat shrouded in mystery. In fact, some scholars are not even sure it ever existed, dismissing it as a mere legend. The most complete references to the fortress and its warriors are found in the Icelandic sagas, particularly inThe Saga of the Jomsvikings" 13th century. After several serious defeats on the battlefield, the power and influence of the Jomsvikings declined, culminating in the siege and destruction of Jomsborg in 1043 by the Norwegian king Magnus Olafsson, also known as "the Good".

One possible location for Jomsborg is in the area of the modern city of Wolin in what is now northwestern Poland, on an island of the same name. Although historical sources seem to point to this area, archaeological evidence does not fully support this. Another possible location may be the island of Usedom near Wolin, on the German side of the Oder River, on land that is now flooded.

8. Norea (Austria)

Situated somewhere on the eastern slopes of the Alps in what is now southern Austria, Norea was described by Julius Caesar as the capital of the kingdom of Noricum. Known to the Romans as Noricum regnum, It was a Celtic kingdom, consisting mainly of the Taurisci; the largest of the Norician tribes. Noricum consisted at its greatest extent of what is now central Austria, parts of southern Bavaria, and northern Slovenia.

As early as 500 BC, the Celts discovered that the iron ore mined in the area produced high-quality steel, and they built a large industry around it. From about 200 BC, Noricum became a strong ally of the Roman Republic, supplying it with superior weapons and tools in exchange for military support. In fact, the Romans came to the aid of the Noricians when their territory was invaded by a large army of two Germanic tribes, the Cimbri and the Teutones. Although the Battle of Norea in 112 BC resulted in a crushing defeat for the Romans, they won the ensuing Cimbrian War.

The exact location of the battle and the capital of the Kingdom of Noricum are still debated. Even Pliny the Elder, who lived in the 1st century AD, already in his lifetime called Noreia a lost city. To further confuse matters, Noria was also the name of the national goddess of Noricum. For this reason, the name could have been given to more than one place.

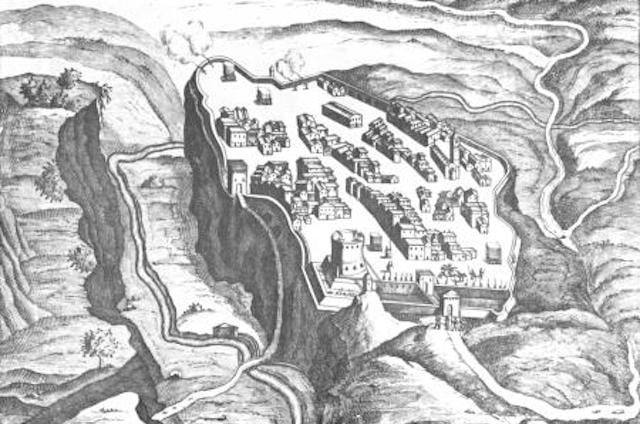

7. Castro (Italy)

Situated in modern Lazio on the western shore of Lake Bolsena, Castro was an ancient city founded in prehistoric times. It was later inhabited by the Etruscans, probably their own lost city of Statonia. In 1537, Pope Paul III created the Duchy of Castro, made Castro its capital, and appointed his son Pier Luigi Farnese as Duke.

The Farnese family was in charge of Holland and the city until 1649, when they clashed with Pope Innocent X over past grievances. The Pope also accused Ranuccio II Farnese of murdering the newly appointed Bishop of Castro and led papal troops into battle. In August, the Duke lost the war and on September 2, 1649, the city was completely razed to the ground by order of the Pope.

As a final act of revenge, the Pope also erected a column amid the smoldering ruins with the inscription What about Castro? (Castro stood here.) The town was never inhabited and is now an overgrown ruin in a picturesque location overlooking the countryside.

6. Euonymus (Scotland)

First mentioned in the 16th century by the Scottish humanist and historian Hector Boece, Euvonium was the coronation site and residence of forty Scottish kings. Euvonium was supposedly built by the 12th king, Even I (98-79 BC), who named it after himself. However, Boece’s writings, which are heavily intertwined with myths and legends, as well as a list of ancient Scottish kings dating back to 330 BC, should be taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, the genealogy of these semi-mythical monarchs existed at least as early as the 13th century AD.

Evonium is widely believed to be located in Dunstaffnage, near the town of Oban in western Scotland. However, Scottish historian A. J. Morton argues that if Evonium had ever truly existed, it would likely have been located in Irvine further south. Among his other arguments, Morton points to Irvine's considerable strategic importance as an administrative and military centre in the Middle Ages, compared to Dunstaffnage's remoteness. He also points to the lands surrounding Irvine, historically known as Cunninghame, which can be translated as "king's house", and the many old Scottish rulers who either came from or lived in the area.

In any case, given the unreliability of the available evidence, Evonium can be seen as a Scottish version of the English Camelot; a legendary and romanticized seat of power instead of an actual historical site.

5. Pavlopetri (Greece)

In 1967, marine geoarchaeologist Dr. Nicholas Flemming discovered the ancient ruins of a long-lost settlement at the southern tip of the Peloponnese peninsula in Greece. Pavlopetri (Paul's Rock) is considered the oldest underwater city in the Mediterranean and one of the oldest in the world.

Initially thought to date back to the Mycenaean period (between 1600–1100 BC), further research has shown that it was inhabited as early as the late Neolithic period around 3500 BC. Archaeological research has also shown that the settlement was a major trading port and had a large textile industry. Graves and chamber tombs have also been discovered, indicating the stratification of social classes in the city. The ruins still retain their original layout, as they have never been built over or affected by centuries of agriculture.

The ancient Greek settlement is thought to have slowly sunk under water after a series of earthquakes lasting many centuries. Researchers estimate that when it was founded, Pavlopetri stood about seven to ten feet above sea level. By 1200 BC, it was only three feet above the shoreline. Further tectonic activity finally dropped it to about 13 feet below sea level sometime between 480 and 650 AD.

4. Vicina (Romania)

Situated somewhere on the Lower Danube in what is now southeastern Romania, the city of Vicina was once the region’s most prosperous trading center. Its greatest asset, but what scholars believe led to its eventual decline, were the region’s particular geopolitical circumstances at the time. Vicina was built by the Genoese as an emporia (trading post) sometime in the 10th century. The city reached its peak in the 13th century, declined in the mid-14th century, and eventually disappeared from records by the late 15th century.

At the time, the Danube Delta was a meeting point between the Byzantine Empire, the Golden Horde and the West. And being located on a major navigable river, Vicina was strategically positioned to conduct trade between them. The Mongol conquest of the area in the 13th century also brought about a relatively peaceful time for the inhabitants, known as the Pax Mongolica, which further facilitated trade. Vicina was ruled at various times by the Genoese, Pechenegs, Byzantines, Mongols, Turks and Tatars, but trade was never interrupted, and on the contrary, all parties benefited from it.

Its decline began after the Genoese-Byzantine War of 1351-1352, when the Byzantines lost their position in the Lower Danube. The power vacuum and increased instability in the region led to a realignment of regional trade routes with the West through the port of Braila on the more peaceful Wallachian side of the river. Some scholars also believe that Vicina’s complete disappearance was the result of a natural phenomenon rather than simply geopolitical factors. Based on some maps and descriptions from the time, they believe that this once-powerful trading center was located on an island that eventually sank beneath the river.

3. Ring (Hungary)

After the death of Attila the Hun, also known asScourge of God , and the collapse of the Hunnic Empire in 469 AD, Europe could finally breathe a sigh of relief. However, this was short-lived, as their place was soon taken by another group of warlike horse lords from the Mongolian steppes, the Avars.

In 567 AD, under King Bayan I, the Avars defeated the Gepids on the Pannonian Plain and made it their home. Incidentally, the Gepids were the same people who had driven the Huns out of there about 100 years earlier. Some sources even say that Bayan killed the Gepid king Cunimund and turned his skull into a wine cup. In the following years, the Avars, under Bayan I, expanded their newly formed Khaganate in all directions, subjugating the local population and using them as “cannon fodder” in their future wars.

According to historian Eric Hildinger, "The Avars had established their headquarters near Attila's old capital a hundred years earlier and fortified it. It was known as the 'Ring.' The name probably comes from its round shape, but little else is known about it. In the following centuries they carried out many raids, especially against the Byzantines in the Balkans, and at one point even besieged Constantinople.

It was under Charlemagne of the Franks, who came to power in 768 AD, that the Avars finally met their match. He led several successful campaigns that eventually pushed the Avars into a disastrous civil war in 794 AD. Charlemagne was then able to easily capture the Ring the following year, which was laden with centuries of plundered treasure. It is said that it took fifteen wagons, each pulled by four oxen, to transport the hoard back to Paris. The exact location of the Avar Ring is unknown, but it is believed to be somewhere in Hungary between the Danube and Tisza rivers.

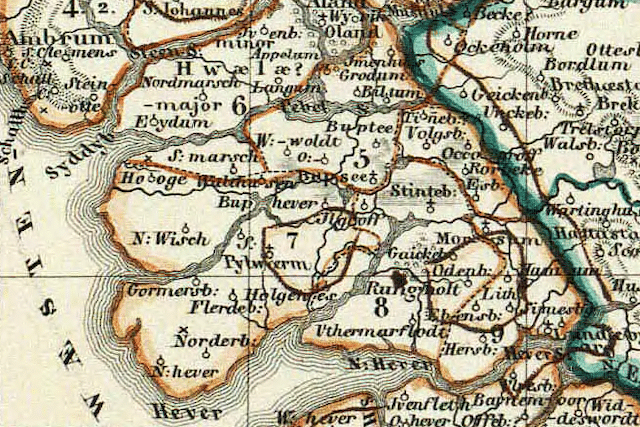

2. Runholt (Germany)

Long considered a local legend and nicknamed by some the “Atlantis of the North,” the town of Rungholt in what is now northern Germany was likely a real place. Although the exact location remains unconfirmed, this once-thriving trading port sank beneath the waves of the Wadden Sea in the second half of the 14th century AD. This was a period of severe storms in the North Sea region that led to the loss of much land, turning arable marshes into tidal flats. The same fate befell the medieval region of Utland in modern-day North Frisia, where Rungholt once stood.

In mid-January 1362, a particularly devastating storm surge known as the Second Grote Mandrenke (2nd St. Marcellus Flood) destroyed more than 30 settlements and killed about 10,000 people in the area, out of an estimated 25,000 people elsewhere on the North Sea coast, Britain, and Ireland. The storm also pushed the coastline back many miles to roughly its current location. Rungholt was the largest of these settlements in the region and an important trading hub between Scandinavia, northern Germany, Flanders, and England. Historians estimate that about 2,000 people lived in the town when the storm hit (a third of Hamburg's population at the time).

1. Tartessos (Spain)

As early as the first millennium BC, Tartessos was known throughout the Mediterranean as one of, if not the richest city of its time. Many saw it as a kind of “El Dorado” of the ancient world. Situated on the southern coast of modern-day Andalusia in Spain, Tartessos was the name of both the region and the supposed port city. The Tartessian culture was a mixture of Phoenicians and Paleo-Hispanics who benefited greatly from the rich deposits of metal ores such as copper, tin, lead, silver and gold.

Thanks to these precious goods, the wealth and glory of Tartessos even made it into the Bible in several chapters. One example can be found in the Old Testament's "Book of Kings 10:20." Testament , where it says that "for the king had a fleet of Tarshish at sea [Tartessian] with the fleet of Hiram: once every three years the fleet of Tarshish came, bringing gold and silver, ivory, monkeys and peacocks."

Speaking of kings, Argantonios (Argantonio in Spanish) was the most important leader of Tartessos, ruling from 630 BC to 550 BC. His name loosely translates as "Silver King" or "Silver One," leading some to speculate that it was more of a title than an actual name.

Given the semi-legendary nature of the historical sources surrounding Tartessos, scholars have long considered it a myth. In fact, due to Herodotus’ description of it being beyond the Pillars of Hercules (the Strait of Gibraltar), some have even gone so far as to say that Tartessos was actually the mythical Atlantis. To further support this idea, the city of Tartessos is believed to have sunk somewhere in the modern-day swamps of the Guadalquivir River, southwest of Seville, which at the time formed a navigable estuary leading into the Atlantic.

Оставить Комментарий