There was a time when there was no greater calling than that of the explorer. So much of the world was still unknown to us, and only a few brave and inquisitive adventurers had to explore the deepest, darkest corners of the planet to illuminate the rest of us.

It was dangerous work, and many lives were sacrificed in this noble cause. As you will soon see, some of the men who explored the unfathomable abyss were never heard from again.

10. The Vivaldi Brothers

ABOUT Vadino and Ugolino Vivaldi little is known . We know that they were two brothers from the Republic of Genoa, living in the second half of the 13th century, and that they were both successful sea traders. We cannot say whether the siblings had a history of exploration and adventure, but in 1291 they set out on a very ambitious voyage - to try to find a sea route from Europe to India via Africa.

In fact, they were looking for the Cape Route, a sea route that crossed the South Atlantic Ocean, skirted Africa at the Cape of Good Hope, and then crossed the Indian Ocean. It had essentially served as the world's most important shipping route for centuries, but the Vivaldi brothers attempted to navigate it nearly 200 years before it was discovered by European explorers.

Suffice it to say, things did not go according to plan. The brothers left Genoa in May 1291 aboard two galleys, possibly named Sanctus Antonius" And " Alegrancia" They were known to have come from the Mediterranean and sailed off the coast of Morocco, but once they had reached the open ocean, nothing more was heard of them.

9. John Cabot

Like the Vivaldi brothers, Giovanni Caboto was an Italian explorer, but he sailed under the auspices of King Henry VII of England, hence the anglicized version of his name - John Cabot . The adventurer made three voyages to England, but it was his second voyage in 1497 that brought him his greatest fame. Known simply as the Cabot expedition, this trip allowed the intrepid explorer to reach the coast of North America, becoming the first European to do so since the Vikings. The exact location where he landed is still debated, although the Canadian government acknowledges Cape Bonavista in Newfoundland, the place where Cabot came ashore.

Since this voyage was successful, Cabot intended to repeat it a year later with the full support of the king. This time he had more ships and they were loaded with goods, which suggested that Cabot wanted to trade.

The fleet left Bristol in May 1498. It is known that one of the ships was damaged in a storm and was forced to return to England. From that point on, the expedition and John Cabot himself simply disappeared from the historical record. Possible outcomes for them included the obvious: they were lost at sea, or they reached Canada but were shipwrecked and lost in Greats Bay on the Avalon Peninsula.

However, some historians believe that Cabot actually returned to England in 1500 and died there a few months later, although this does not really explain why there is no mention of his return or death.

8. Henry Hudson

A hundred years after Cabot, another explorer sailed under the English flag and explored the northeastern coast of North America. This was Henry Hudson, the man who gave his name to the river Hudson , Hudson Strait and several other places.

There are many similarities between Henry Hudson and our previous entries. Like Cabot, he made several successful voyages to the New World in the early 1600s. Then, like the Vivaldi brothers, Hudson embarked on a very ambitious mission that would prove his undoing. In his case, it was to find the Northwest Passage, a sea route that connected the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans by passing through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago.

The first person to successfully complete the route was Roald Amundsen in 1906, so we already know how things went for Hudson, who attempted it 300 years ago. The explorer set out from London in 1610 aboard the Discovery» with a crew of 23, including his son John Hudson. He reached the Arctic Ocean, but became trapped in the ice of James Bay, and had no choice but to go ashore and wait out the winter.

Miraculously, the expedition lost only one man in the coming months, but by the time spring arrived, most of the crew wanted to go back to England. They mutinied and put Henry Hudson, his son, and seven loyal shipmates in a boat and cast them adrift, never to be seen again.

7. La Perouse

In the late 18th century, the Age of Enlightenment was in full swing, and scientific exploration expeditions were the new hot ticket. Following the voyages of James Cook, France felt it was falling a bit behind England, so in 1785, King Louis XVI ordered his government to organize a circumnavigation expedition and complete Cook's exploration of the Pacific Ocean.

The leader of this scientific mission was Jean-François de Galaup, Count of La Pérouse, a senior naval officer who had distinguished himself in battles against England during the Seven Years' War and the American Revolution. La Pérouse was given command of two frigates: The Boussole And Astrolabe — fully equipped with the most modern scientific equipment of the time, as well as a significant library and a team that included several scientists.

The expedition left France in August 1785 and for three years things went very well. La Pérouse began by sailing to South America, then rounded Cape Horn and sailed as far north as Alaska. He then crossed the Pacific Ocean and reached East Asia before heading south to Polynesia. In January 1788, the two ships reached Australia, where they were docked for a month and a half. They left in early March and were never seen again.

Their disappearance was considered a national tragedy in France, and several rescue operations failed to find any trace of what had happened to them. Even King Louis XVI was reported to have asked his captors on the day of their execution as they were being carried to the guillotine if there were any news about La Perouse .

It was not until nearly 50 years later that sailors discovered remains that suggested both ships had crashed on the reefs of Vanikoro Island and sunk, but that still did not explain the fate of the crew. Local oral history says that the survivors spent months on the island building a schooner before setting out to sea again and disappearing again.

6. Douglas Clavering

Scottish naval officer Douglas Clavering made his name as an Arctic explorer, leading an expedition to Greenland and the Spitsbergen archipelago in 1823. However, this had nothing to do with his mysterious disappearance. After his successful return to England, Clavering received another commission as part of the West African squadrons , a recent British anti-slavery initiative.

The squadron was formed in 1808 following the passing of the Slave Trade Act and consisted of a fleet of Royal Navy ships that patrolled the waters off the coast of West Africa in an attempt to suppress slavery. Captain Clavering joined the squadron in 1825 after being appointed to command the brig-sloop HMS Redwing .

Although the West African Squadron captured some 1,600 slave ships during its 50-year existence, little is known about Clavering's personal involvement. What we do know is that two years after his appointment, Redwing" sailed from Sierra Leone, andno one saw him again Pieces of debris washed up on the shore suggest the ship may have caught fire, possibly from a lightning strike.

5. Baron von Toll

In 1900, the St. Petersburg Academy of Sciences commissioned geologist and explorer Baron Eduard von Toll to lead a new Russian polar expedition to the Arctic to explore an archipelago called the New Siberian Islands. In particular, he was to find the mythical Sannikov Land and prove once and for all whether the island actually existed.

The landmass had first been discovered a century earlier, and several explorers had claimed to have seen it since, including von Toll himself on an earlier expedition. This made him ideal for this mission, so in June 1900 he set out for the Arctic with a crew of 19 on board. Dawn » .

Unfortunately for von Toll, Sannikov Land did not exist, and that was his undoing. After two years in the Arctic, his crew had collected a wealth of scientific data, but no sign of the elusive island. As the expedition neared its end, von Toll decided on one last daring adventure. After the winter of 1902, he and three crew members abandoned the "Dawn" and set out on a separate voyage by sledge and canoe to make it easier to maneuver through the archipelago. They were to meet the rest of the crew at Bennett Island , but thick ice prevented the ship from getting any closer. From that moment on, the fate of von Toll and his three crew members became a mystery. Several months later, a search party found their camp on Bennett Island, along with several notes written by the explorer, but no trace of the people was ever found.

4. Joshua Slocum

In 1898, Canadian explorer and adventurer Joshua Slocum became a worldwide sensation when he became the first man to sail solo around the world. He spent the last three years sailing 46,000 miles aboard his sloop, Spray" . Slocum then wrote an account of his experience entitled, Sailing around the world alone ", which became an international bestseller.

Slocum's success also gave him some financial stability, which allowed him to buy some land and settle down. However, the old sea dog soon realized that he felt more at home on the open ocean than on solid ground, so he resumed sailing, often traveling between the United States and the West Indies or South America.

Unfortunately, it was one of these trips that led to Slocum's demise. In November 1909, he left Massachusetts for the Caribbean on his trusty vessel "Spray" . He was last seen to replenish supplies in Miami , before he disappeared. Neither the man nor the ship were ever found. While the obvious scenario is that Slocum died at sea, especially since he apparently never learned to swim, another theory suggests that the adventurer faked his disappearance in order to start a new life away from his family.

3. Roald Amundsen

In the pantheon of polar explorers, the name Roald Amundsen probably rings louder than any other, but even he did not escape an untimely and uncertain death.

In 1906, Amundsen led the first expedition to successfully navigate the Northwest Passage. Five years later, he became the first person to reach the South Pole. These were his two biggest claims to fame, but Amundsen remained involved in Arctic exploration until the very end.

May 25, 1928 somewhere on the Spitsbergen archipelago, a shipwreck occurred polar airship " Italy" . This sparked an international rescue operation that included the ageing Amundsen, who boarded the prototype Latham 47 flying boat with a crew of five to help search for the wreckage. The plane took off from Tromso, Norway, June 18 and disappeared without a trace over the Barents Sea.

The wreck of the Italia was eventually found and many survivors were rescued, but the same could not be said for Amundsen's Latham 47. Even modern searches using the latest sonar technology And Submarine searches have yielded no results, so for now the final resting place of one of the greatest Arctic explorers remains a mystery.

2. Michael Rockefeller

Michael Rockefeller was born into the fabulously wealthy Rockefeller family, but unlike his predecessors, he avoided the world of business and politics and preferred a life of adventure.

After studying history and economics at Harvard, Rockefeller became interested in ethnology and anthropology. In 1960, he joined the expedition as a sound engineer V documentary about the Dani people of Western New Guinea, then part of the Netherlands. While there, Michael encountered another group of people called the Asmat, who fascinated the young Rockefeller with their artwork.

The following year, he financed his own expedition back to New Guinea, hoping to study the Asmat people in detail and even organize an art exhibition in New York. The team consisted of just him, a Dutch anthropologist. Rene Wassinga and two local Asmat teenagers. Over the course of three weeks, the expedition went well as Rockefeller visited and traded in 13 different villages, amassing a significant collection of Asmat artifacts.

Something went wrong on November 16, as the crew was sailing downriver to a nearby village. Several strong waves and currents capsized the boat, plunging all four men into the water. Two Asmat teenagers quickly swam to shore and went for help, but Wassing and Rockefeller had no choice but to cling to the overturned raft and drift downriver. After a full night of stranding, Rockefeller tried to make it to shore… and that was the last time he was seen. Wassing was spotted by helicopter and rescued the next day.

Rockefeller's official cause of death was drowning, but in later years there were rumors that he was actually killed and eaten by people from a village called Otsjanep However, by that time Western New Guinea was no longer part of the Netherlands, so no official investigation was carried out.

1. Peng Jiamu

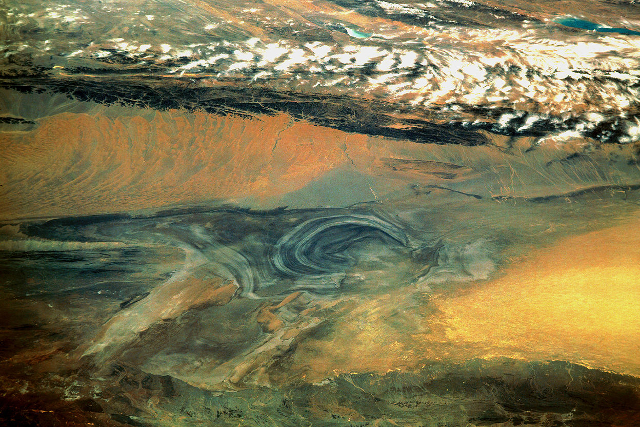

We end with the very last item on our list, which shows that even in our time there are still many unknown parts of the world that harbor hidden dangers. By 1980 Peng Jiamu had already established himself as one of China's leading biochemists, having taken part in numerous scientific expeditions over the previous 25 years to explore the country's wildest and most remote regions. That same year, he set out to explore Lop Nur, a desert in the Tarim Basin. Five days into the mission, Peng vanished without a trace, seemingly swallowed up by the vast emptiness of the desert.

It turned out that the scientist had left camp alone in the middle of the night to look for water and had gotten lost in the desert. This was very puzzling, considering that Peng was an experienced explorer who would have known better. Add to this the fact that an extensive search by the Chinese government had failed to find any trace of him, and it raised several eyebrows. conspiracy theories , who suggested that Peng may have been killed by his colleagues, kidnapped by the Russians or Americans, or even defected of his own free will. The truth remains a mystery.

Оставить Комментарий