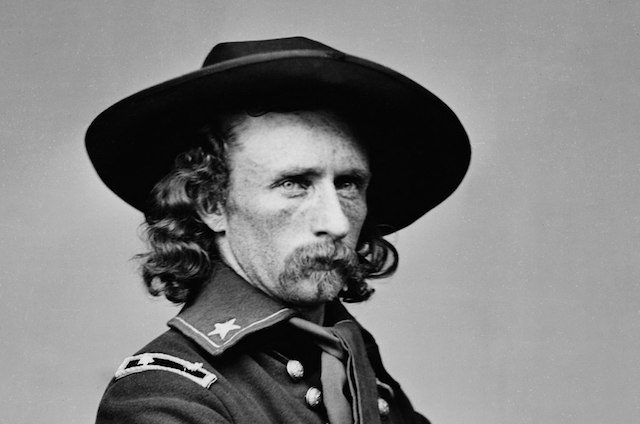

Few of the legendary heroes of American history are more controversial than Caster . At that time, he had accumulated many deficiencies as a cadet at the United States Military Academy and ranked last in his class in academic performance. However, two years after graduation, he was promoted to brevet (temporary) brigadier general of volunteers. He was the youngest general in the American army since Lafayette. During the Civil War, he earned a reputation for superior leadership, sound military tactics, and personal courage in leading his troops from the front.

After the war, when he was sent west to help pacify the western tribes, his reputation plummeted. He achieved almost mythical martyr status after his death at Little Big Horn, largely thanks to the efforts of his widow , Libby Bacon Custer. Movies and early television exaggerated his myths. Then, beginning in the 1970s, changes in American history regarding Native Americans once again diminished his lofty hero status. Here are ten incidents from the life and death of George Armstrong Custer that contributed to his myths and remain controversial.

10. He didn't do very well at West Point.

Later in his military career, George Armstrong Custer wrote that those who accepted his behavior should ignore his career at West Point unless they viewed it as “…an example to be carefully avoided.” He arrived at the Military Academy with a minimal education in mathematics, although he had some experience as a schoolteacher in other subjects. He also had a lifelong penchant for practical jokes and an established disdain for higher authority. Neither of these traits indicated guaranteed success in a highly disciplined environment, renowned worldwide for the quality of education, which she gave to her cadets.

He excelled, if that's the word, in one area of school. During his four years at West Point, he accumulated a record number of fines at the time. for various violations. He kept his cooking utensils in the barracks. One afternoon in Spanish class, Custer asked how to say "Class dismissed" in that language. When the instructor said the phrase, Custer grabbed his books and walked out of the classroom. His uniform was improper, his hair was too long, and his shoes were not polished enough, far from the dandy he would later become.

Like many cadets of the time, Custer frequented a nearby tavern. Benny Havens, officially closed, but popular nonetheless. He also became known among the cadets and staff for his horsemanship. In June 1861, the planned five-year term for his class was reduced to four, and Custer graduated. His tenure at West Point was well known to the officers with whom he served, both the senior officers who preceded him at the Point and the cadets who followed him, in awe of the legendary record of avoiding harsh punishment that he left behind.

9. Northern newspapers extolled him at the beginning of the Civil War.

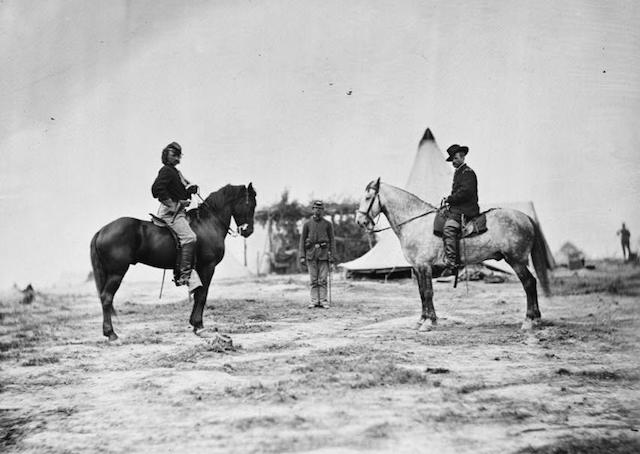

Caster graduated from West Point in 1861 , a year earlier than planned, because of the need for trained officers for the rapidly expanding Union Army. At that stage of the war, Union battle victories were rare, and Confederate troops were camped just thirty miles from Washington, Virginia. Custer distinguished himself at the First Battle of Bull Run. He then fought in the Peninsula Campaign, the Maryland Campaign, and the Battle of South Mountain. He led numerous cavalry charges, served as an aide to General George McClellan, and earned a reputation as a daring field commander. In June 1863, as Confederates under Robert E. Lee advanced into Pennsylvania, Custer was given command of the Michigan Cavalry Brigade as a brigadier general of volunteers. He was 23 years old.

His success in the early campaigns brought him to the attention of Northern newspaper reporters and magazine correspondents. As a commander, using his rank, Custer adopted a colorful uniform, much to the delight of scriptwriters. He justified his appearance as a necessity on the battlefield, making it easy for his officers and men to identify him, as well as for messengers from other units to find him in the chaos of combat. During the three-day Battle of Gettysburg, Custer led his unit, the Wolverines, into a decisive battle with the almost legendary Confederate cavalry under Jeb Stuart, who was attempting to outflank the main Union army. Despite being heavily outnumbered, Custer led his command to victory, driving the Confederates from the field.

In reports from the Gettysburg campaign, Custer received lavish praise for his performance. His bright clothes in battle attracted the attention of his enemies, as well as his friends and commanders. The newspaper New York Herald called him "the boy general with the golden locks." His unit suffered heavy casualties during the campaign, and at least one of his horses was shot during the fighting. Newspapers extolled his leadership, always from the front, and his personal courage. Custer became a celebrated hero in the North, and his reputation was enhanced by his later actions during the Civil War.

8. Custer stole a horse and refused to return it when ordered.

By early 1865, Custer commanded a cavalry division as a major general and maneuvered it to block Lee's escape at Appomattox. There, he learned of a valuable thoroughbred racehorse owned by Richard Gaines near Clarksville, Virginia. Custer sent a patrol to retrieve the horse, along with its written pedigree. Lee had surrendered more than two weeks earlier, and the terms of the surrender allowed his defeated army to keep the remaining horses. Custer didn't care; he had heard much about a fifteen-hand stallion named Don Juan. His determination to obtain the pedigree, which would be necessary to later sell the animal for its true value, suggests that Custer had come to a deliberate decision to steal a horse .

Custer rode Don Juan in the Army of the Potomac's Grand Parade in Washington, D.C., when the skittish animal fled from the crowd's noise. The horse's sudden charge allowed Custer, known for his long blond hair, to demonstrate his horsemanship to an adoring crowd. Grant later ordered Custer to return the animal to its rightful owner. Caster refused , supported by Philip Sheridan, insisting that the animal was contraband of war and that he had purchased it legally from the Union Army for his own use.

For Custer, the horse represented the spoils of war, and he wrote in several letters that he intended to sell the animal, believing it could fetch him $10,000 ($176,000 today), a substantial sum at the time. The horse died suddenly in 1866, ending Custer's hopes for a life savings. Custer's behavior upon receiving the horse and his seeming impudence in refusing to return it, despite being ordered to do so, deepened the rift between him and General Grant. Although the story was not widely known to the public at the time, gossip circulated among officers about Custer's theft from military posts. Today's Custer State Park, located in the shadow of Mount Rushmore, contains among its treasures a lake ironically named Horse thieves' lake.

7. Custer used his fame in post-war New York.

After the Grand Parade, Custer returned to his hometown of Monroe, Michigan, to rest. Custer then assumed command of the Federal cavalry in Louisiana, which was destined to form the basis of the occupation forces in eastern Texas. His command there was difficult. Most of the troops were volunteers who wanted to get out of the service because the war they had volunteered for was over. Custer's attempts to maintain discipline among the troops had caused discontent, desertion, and outright mutiny. He also found that he no longer had the support of U.S. Grant after his disobedience over Don Juan and other issues.

Released in early 1866, Custer was sent to Washington , where he lobbied for the appointment. He considered a career outside the military, traveling to New York to mingle with high society and industrialists. He also requested a furlough to allow him to travel to Mexico and support Benito Juarez's forces in the Mexican Revolution. Grant supported his request, but Secretary of State William Seward opposed it, and Custer remained unemployed in Washington with the permanent rank of captain.

In the summer of 1866, Custer joined President Andrew Johnson, along with other Civil War heroes such as Grant and Admiral David Farragut, on a campaign tour to build public support for Johnson's Reconstruction policies. It was the first time an American president had run a national campaign along party lines. proved disastrous for the president Grant refused to speak to the crowd, and Custer spent much of his time lobbying the president for promotion and command in the West.

6. The 7th Cavalry Regiment was a new unit when Custer was appointed its commander.

In films and television adaptations of the Custer myth, especially those produced before 1970, 7- y cavalry regiment Castera usually depicted as a mounted regiment. In fact, the US Army created 7- y cavalry regiment in July 1866 as part of a general expansion of the regular army. Custer was not the first commander of the 7- go cavalry regiment. Colonel Andrew Smith took command and organized a new regiment at Fort Riley, Kansas. In February 1867, Custer arrived at Fort Riley and assumed command of the regiment with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Less than a year later, Custer was relieved of command without pay after an unsuccessful pursuit of hostile Indians that resulted in several desertions. After returning to his regiment and command, he was again relieved of command and arrested in August 1868, having gone AWOL (without leave) when he abandoned his post against orders. He remained suspended until October 1868, when he returned to his command on the orders of Philip Sheridan , who then commanded the entire United States cavalry.

By 1869, Custer's once vaunted reputation was in ruins. He angered US Grant. , several members of Congress, and several of his fellow officers. Many of the junior officers disdained his flamboyant appearance and the fact that he was often chased by several dogs. Nevertheless, he retained Sheridan's support, and, certain that his star was falling, he craved a major victory over the Indians that he could use for public recognition.

5. The Washita River restored Custer's reputation in the East.

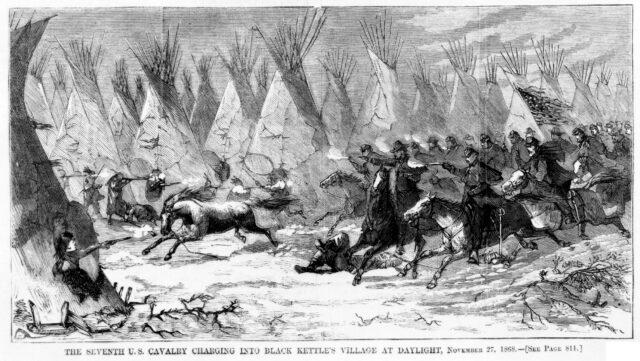

Custer won what was considered the first major victory over the western Indian tribes when he led the 7th cavalry regiment for Attacks on a Cheyenne village under Chief Black Kettle in November 1868. village. Black Kettle stated during negotiations with Indian agents and military that his people wanted peace. However, warriors from several bands of bandits left his village and returned there during the summer and fall months.

Actions Washita has long been controversial . In the 1960s and 70s, Indian activists claimed that the battle was little more than a massacre, mostly of women, children, and older men. They claimed that there were few, if any, warriors in the village at the time of the attack. Custer initially claimed that 103 warriors were killed, later increasing the number to 140. He acknowledged "a few" female casualties and reported 21 soldiers from the 7th Regiment killed. And another 13 wounded.

Attack on the Washita River restored Custer's reputation in Eastern newspapers and among the general public as a courageous cavalry leader and a tough Indian fighter. However, during the battle he retreated before learning the location of a small force sent to pursue the fleeing Cheyenne. This group encountered warriors from other nearby camps and was heavily outnumbered, routed, and killed. The incident led to deeper suspicions among junior officers that Custer had put his quest for glory above the welfare of the men under his command.

4. Custer's defeat at Little Big Horn shocked the entire country.

In the summer of 1876, the United States began its long-planned celebration of the nation's centennial. Passenger railway excursions to Philadelphia on exhibition of the century , held there from May 10, were almost always full. So were the steamships and ferries that carried visitors to the first World's Fair. Among the items introduced at the fair were Hires Root Beer, Heinz Ketchup, and a communication device that its inventor called a telephone.

Americans celebrated their national unity, new technologies, and the vast wealth of the continent. Revelers at the fair, those who traveled to it, and those who stayed home were shocked by the news Custer and his command at Little Big Horn were destroyed by Indians. The exhibition featured numerous examples of modern military weapons, including those from Germany and France, as well as the United States. The prevailing public opinion of the time about the Indians made it unthinkable that they would defeat a disciplined detachment of American cavalry.

The shock led to an immediate decision to crush the Indian tribes that had destroyed Custer's command. By the spring of 1877 Cheyenne under Chief Dull Knife were defeated, their villages destroyed, and they were forced onto reservations. There is little evidence that Dull Knife was involved in the Little Big Horn. The Sioux, Arapaho, and other Plains tribes were also crushed and forced onto reservations. Many tribes were driven into Indian Territory, as it was then called, in what is now Oklahoma. A significant number of Sioux, led by Sitting Bull, fled across the border into Canada.

3. His widow, Libby Bacon Custer, worked tirelessly to cement his heroic reputation.

In the United States Army, right up to its Commander-in-Chief, President Grant, Custer received little praise immediately after Little Big Horn. Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen, both of whom survived the battle because they were not with the five companies Custer personally led, blamed him for the defeat. Reno had a checkered career after Little Big Horn, including charges of flirting with another officer's wife, drunkenness on duty, and the worst charge of all against a military officer: cowardice before the enemy.

Benteen, who had been ordered to reinforce Custer's command during the battle, rode instead to support Reno. He, too, blamed Custer for the debacle at Little Big Horn. Few in the Army's command structure defended the actions of the dead Custer. President Grant publicly condemned Custer for his actions and the loss of life that followed. Without the support of his late husband Libby Bacon Caster stepped into the void. Libby kept detailed diaries of her life with her husband on the American frontier, where she accompanied him to his posts.

Libby polished and published her diaries in the 1880s; Boots and saddles (1885), Tents on the plains (1887) and In the footsteps of Gvidon (1890). Her books aimed to give Custer a splendid image, and they were for the most part historically correct, except for details concerning maneuvers in the field. They enjoyed wide popularity, and were soon supported by dime novels and dime newspapers, and the Custer legend, like that of the Last Stand, was brought into the public eye. Artists produced paintings of Custer fighting heroically to the death, including painting commissioned by Anheuser Busch , which hung in saloons across the country. The legend of "Custer's Last Stand" survived untarnished for nearly 100 years.

2. Caster in Film and Television

Beginning with a silent film in 1912, Custer starred in films more than 30 times , featuring a number of prominent actors. Ronald Reagan played Custer in the entirely fictional film " Santa Fe Trail" (1940) The following year, Errol Flynn heroically portrayed Custer (how else could Flynn play anyone?) in They died with their boots on." . Several films have depicted Custer as defending the rights of Indians against nefarious government agents, illegal traders, and corrupt officials who exploit them. In 1967, Robert Shaw, who later starred in "Jaws" , played Custer, who risks his military career to protect Indian rights in " Caster of the West "The legend of the Last Frontier has remained very much alive.

During the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 60s, historians and filmmakers began to reexamine the Custer legend. An early example is "Little Big Man" 1970s years starring Dustin Hoffman. A fictional story told through the eyes of a white man raised by the Cheyenne, it was intended in part to satirize the military establishment at the height of America's involvement in the Vietnam War. Richard Mulligan portrayed Custer as a frontier psychotic, driven by a deep hatred of Indians and finally driven completely insane during the climactic Battle of the Little Big Horn.

Television has largely followed the same pattern, with early programs portraying him as a heroic icon of American history, and later depictions making him rebellious, selfish, and determined to destroy tribes to gain greater glory for himself. Whether sympathetic, critical, fictional, or even parodic, Custer remains a popular character in television productions, including the series "Absurdity 6" from Netflix , released in 2015. Caster was played by David Spade. The production earned some of the most harsh reviews in the history of cinema.

1. The natives of that time respected Custer.

Although some revisionists dispute this, troops under General Terry who recovered the bodies of Custer's men found them horribly mutilated. With the exception of two, Custer and Miles Keogh. Keogh was allegedly spared because he was wearing Religious medallion from the Papal States. Superstition among the natives probably led them to respect the medal. Custer's eardrums were reportedly punctured, but his body was unharmed. Terry's men found two wounds to the head and chest. Either wound could have been instantly fatal. Some claim that an arrow was found in Custer's genitals, although this is not officially reported.

Most of the crew members who died were horribly disfigured Custer's brother Tom, a two-time Medal of Honor recipient, was so disfigured that he was identifiable only by a portion of his tattoo. Custer's body was more or less abandoned in the fall, though his eardrums were punctured, according to tribal folklore, which they believed would make him deaf in the afterlife. The fact that his body was spared the indignities of the rest of his command suggests that his enemies held Custer in high regard, a level not shared by those who continue to rewrite the story of his career and death.

Custer was buried with the rest of his men as they lay on the field. Attempts to identify them at the time were hampered by their mutilations and the looting of their personal belongings by their killers after the battle. Custer's body was later exhumed and reinterred at West Point in October 1877. By then, the U.S. military's efforts to defeat the western tribes that dominated the Little Big Horn were well underway. For the Native Americans, the Little Big Horn (which they called "Greasy Grass") had won a Pyrrhic victory. By the end of the decade, the Plains Indian tribes had been subdued, and a reexamination of their history had begun.

Оставить Комментарий