Idioms are one of the most intriguing and colorful parts of human language, but also one of the most infuriating for linguists. Many of these expressions are decades or even hundreds of years old, and trying to trace them back precisely to their origins is often frustrating.

In doing so, we're going to take a look at the interesting origins of ten popular idioms as we know them.

10. Bury the hatchet

« Bury the hatchet " means to end a disagreement and become friends again. This expression has been around for hundreds of years, and the most early references in print they date back to the mid-18th century.

This refers to an even older custom among several Native American tribes, who would literally bury their hatchets and other weapons after a period of warfare to show that they were now at peace. Given how much of Native American history was passed down through oral tradition, it’s really impossible to say exactly how long this custom or expression has been around. However, one old legend links it to a seminal pre-colonial moment in North America, when the Five Nations—the Mohawk, Onondaga, Oneida, Cayuga, and Seneca—agreed to the Great Law of Peace and formed the Iroquois Confederacy.

According to the tale, the tribal leaders collected their weapons and placed them under the roots of a giant white pine , thus burying their hatchets and celebrating peace.

9. Jumping the Shark

« Jumping the Shark " is a much newer idiom than the others on this list. It is also an experience that all TV series want to avoid. It refers to a moment that marks a shift in the show, followed by a noticeable decline in quality. It is usually marked by some ridiculous or out-of-place event that viewers perceive as a desperate attempt to make the series feel new and fresh again. Notorious examples include the addition of Cousin Oliver in the Brady Bunch , Bobby Ewing's death shown as just a dream in Dallas , or an attempt to replace Mulder in The X-Files two new agents.

But here, of course, there is an original moment, the one in which you literally had to jump over the shark. In the episode "Happy Days" 1977 The Fonz water skied down a ramp and jumped over a shark in his signature black leather jacket. The term was coined in 1985 by a radio host John Hein , and that's how television history was made, though not necessarily for the better.

8. Peeping Tom

If someone is a bit of a pervert who likes to peek at lewd things he shouldn't see, you might call him a "Peeping Tom." But who is this Tom, and what did he see that forever branded him a degenerate?

The term comes from a legend about naked ride Lady Godiva . In case you need a quick refresher, Godiva was the wife of the 11th century Anglo-Saxon nobleman Leofric, Earl of Mercia. While begging him to lower taxes on the poor of Coventry, Leofric told Godiva he would do so if she would ride around the town naked. His wife agreed, and during her naked stroll, all the townspeople averted their eyes out of respect for Godiva. Everyone except pervert Tom, of course, who couldn't help but take a few quick glances. And from then on, he was known as Peeping Tom .

It's probably worth noting that, aside from the historical existence of Godiva and Leofric, everything else is just a legend that has been built up over the centuries. It wasn't until hundreds of years later that Peeping Tom even entered the picture. We have no idea if the trip ever actually happened, but if it did, it's unlikely that Peeping Tom was a real person.

7. Close, but without a cigar

If you have almost succeeded at something but failed just before the end goal, you may hear someone offer you these wise words: “ close but no cigar ".

There is no definitive evidence to suggest the origin of this idiom. The earliest known appearance in print is in an issue of Long Island Daily Press for 1929 However, most people believe that the expression was a little older and came to us from American carnival games sometime in the late 19th or early 20th century.

At the time, most of these games were aimed at adults rather than children, and they probably wouldn't be too interested in winning a cheap stuffed animal. So adult rewards were offered, and cigars were one of the most common prizes. Because many of these games were rigged in such a way that participants were often on the verge of winning before failing, the expression "close, but without a cigar " was meant to serve as a consolation and also to encourage the player to perhaps pay and play again.

6. White elephant

« "White Elephant" — is a term used to describe a burdensome possession, often very expensive to maintain and generally more trouble than it's worth. This is another idiom whose exact origin is unknown. For the first time He appeared in English print around the mid-19th century, but it is believed to have originated in Siam, today known as Thailand, where the term was quite literal.

The white elephant was a rare and sacred animal that kings kept in their court because it signified peace and prosperity. As such, it was incredibly valuable, but as you can imagine, actually caring for one was labor-intensive and expensive. If you were a king then of course no problem, just get your servants to do it, but if you were anyone else, then actually owning a white elephant could ruin you financially. While there is no hard evidence to back this up, history has it that some kings of Siam intentionally gave white elephants to people they didn't like in order to send them to the poorhouse.

5. Horse riding

Whenever a group of people go for a drive, they already know which seat in the car is the best: the front passenger seat. You get the best of both worlds: you get a view, access to music, and you don’t have to actually pay attention or drive. So the unspoken rule of the road is that passengers can vie for this spot by “calling shotgun,” and those who sit in the front passenger seat are said to “ride shotgun.”

Riding a shotgun dates back to the days of the Wild West, when stagecoaches had to cross the frontier and often fell prey to outlaws, Native Americans, and even wild animals. That's why the job title " shotgun messenger " - a security guard who will ride next to the driver, armed with, as you may have guessed, a shotgun.

While the practice certainly existed during the Wild West, whether people actually used the phrase "riding shotgun" back then is still a matter of debate. So far, the earliest printed example of the idiom was found in a 1905 novel called Sunset Trail" . But this term proved popular in westerns early Hollywood and became inextricably linked with the Old West.

4. Bob is your uncle

"Turn left, go straight ahead to the crossroads, turn right, and Bob will be your uncle! You have arrived at your destination." In this case, "Bob is your uncle" functions as a kind of interjection, denoting , how easy a task like "piece of pie" should be, but it raises one important question: who the hell is Bob?

However, this question is not so easy to answer, because there are several stories about the origin of his peculiar idiom. By far the most popular is the tale of blatant political nepotism, which claims that Bob was none other than Robert Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury and Prime Minister of the United Kingdom in the late 19th century. The expression supposedly refers to his nephew To Arthur Balfour , whom he appointed to several posts for which he was unsuited, including Chief Secretary for Ireland. Balfour's critics regularly suggested that he owed his entire political career to good old Uncle Bob.

This is a plausible explanation, but the idiom does not appear in print until decades later. The earliest written example is believed to have been in a Scottish newspaper in 1924, in the bill for a musical revue called Your Uncle Bob" . Then, in the early 1930s, we have its final appearance in a song by music hall singer Florrie Forde. But in both cases, we have to assume that the phrase was already in common use, and not just made up, meaning that the true origins of the idiom are still up in the air.

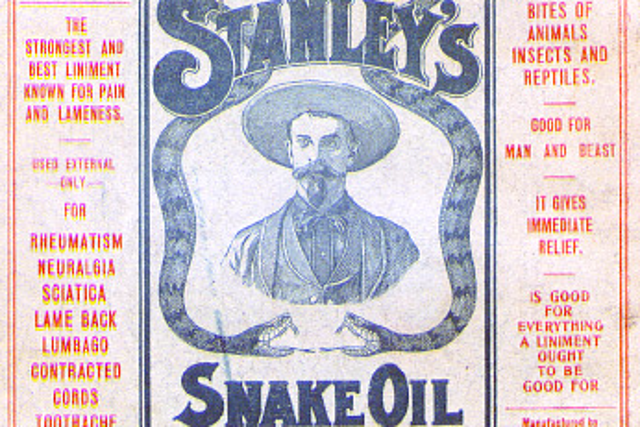

3. Snake Oil Salesman

Nowadays, a snake oil salesman is a person to generally avoid because the term refers to a shady con man peddling some kind of quack cure. But there was a time when that wasn't necessary. Snake oil was a genuinely useful medicine, but one man ruined it for everyone and changed the meaning of the phrase forever. And that man was Clark Stanley , "The Rattlesnake King."

Traditional medicines made using parts collected from snakes have been around for thousands of years. In this particular case, “snake oil” refers to an ointment made from the oil of Chinese water snakes, which was brought to America in the 19th century by thousands of immigrants who came from China. This type of snake oil was the real deal. It was used to treat arthritis and bursitis , and even modern tests have concluded that it has therapeutic benefits , as it acts as an anti-inflammatory. However, once the product became popular, all sorts of people began selling it, and since there was virtually no regulation at the time, they could put almost anything they wanted in the bottles they sold.

Things changed after the Pure Food and Drug Act of 1906, which sought to curb the use of patent medicines. It took them a while, but ten years later they finally got around to snake oil. They took one of the most popular snake oils — Clark Stanley's Snake Oil Liniment .

Stanley liked to call himself the "Rattlesnake King" because he used rattlesnakes for his product, as Chinese water snakes were a bit thin on the ground in Texas. At least that's what he claimed, but when authorities analyzed his product, they found that it was mostly mineral oil mixed with some tallow oil and additives. There wasn't a drop of snake oil in it.

For his deception, Clark Stanley received a draconian fine of $20, but he destroyed the credibility of the snake oil industry and gave us the term we know and use today.

2. Read them the law on riot

"Our Sovereign Lord the King commandeth and commandeth all the people assembled to disperse forthwith, and peaceably return to their dwellings, or to their lawful business, on account of the hardships contained in the act made in the first year of King George's reign for preventing riots and disorders. God save the king !»

We just read you the riot act. It was real. Riot Act 1715 or at least the part of it that had to be read out loud before people were given a 60-minute grace period to disperse. If they didn't, they would be committing a crime and being arrested.

These days, "reading someone a riot act" means giving them a proper reprimand or admonition, but back then, the crime could carry the death penalty execution If this seems a bit harsh, it’s because George I was the first English king from the House of Hanover. The previous dynasty, the House of Stuart, still had many supporters, and there had already been some violent riots during George’s coronation. The Riot Act was a radical measure aimed at preventing more violent outbreaks by banning people from gathering in groups of 12 or more.

1. Steal My Thunder

Last but not least, we have the phrase "steal" your thunder ", meaning to deprive someone of praise or attention by doing or saying something they intended to say or do. It's nice to end the idiom with a fair amount of certainty—we know who said it first and even when they said it, although the wording is a little vague.

This one dates back to the early 18th century. The English critic and essayist John Dennis also aspired to be a playwright, though not so much for his writing talent. In 1709, he wrote and produced a new play, Appius and Virginia" The audience responded with apathy and the show was soon closed, but Dennis had gotten one thing right - a new kind of thunder machine.

At the time, the most common way to simulate thunder was for a stagehand to shake a sheet of metal, a technique that is still used in the theatre today. We don’t know how John Dennis’s idea worked, but apparently it was good enough to be stolen. One night, he attended a production of Macbeth" in the same theater where they were cancelled "Appius and Virginia" , and heard the distinct noise of his invention. At that moment he jumped up from his seat and shouted:

"It's my thunder, by God! The villains won't play my play, but they steal my thunder ".

Оставить Комментарий